The War of the Apes, 1975

- alanageday

- Aug 10, 2024

- 3 min read

Jane Goodall lived in Bournemouth, England. She was a happy and playful child, but above all else she was curious and hungry for knowledge. The illustrated books on natural sciences, botany and travel that she found in her father’s study, those great tomes encased in brown leather with engravings and sketches that she set open upon her knees, were precious vehicles of escape amidst the ceaseless rain of this grey English town. Little could she imagine that one day she would spend her life studying the evolution of chimpanzees in Kenya and Tanzania. Jane Goodall only knew Africa through her books and her dreams of adventure. Children attach great importance to the first toys they receive from their father, or the first dolls given to them by their mothers. For Jane’s fourth birthday, her father gave her a stuffed chimpanzee toy, which she would name Jubilee. “What a horrid thing!” squealed her schoolmates. “Why not a bear? You’ll have nightmares!” exclaimed her grandmother. “Jane likes exotic animals, and I like to see her happy,” replied the father, proud of his little girl’s curiosity. And so Jane formed a bond of friendship with the chimpanzee. She took Jubilee to bed with her, and sometimes even offered her a glass of milk. But her favourite pastime was climbing trees with Jubilee. She sat on the highest branch of the poplar in the park and imagined they were in the jungle surrounded by lush vegetation, listening to the cries of wild animals and watching the venomous snakes slithering along the branches.

In 1974, the Gombe War broke out in the Tanzania National Park. Its belligerents were two tribes of chimpanzees: the Kasakelas and the Kahamas. The chimpanzees fought a war between the north and south of the valley. The Kasakelas were greater in number, with eight adult males, while the Kahamas had six adult males. The war between the two tribes was officially declared on 7 January 1974, when six adult males from the Kasakela tribe murdered a male of the Kahama as he was feeding in a tree. Jane Goodall, a primatologist and anthropologist, considered to be the leading authority on chimps, was quickly brought in to analyze the phenomenon and try to determine why this brutal war was taking place. She took the first plane from London to Tanzania, her luggage loaded with books, notes and studies. She arrived at a camp in the middle of the valley, and had a team of rangers assigned to her. Now her work could begin. During her study of this war, she remarked that the “the chimpanzees of Gombe are rather nicer than humans.” The chimpanzees of Gombe had feelings; as they could distinguish night from day, so they could be sad or joyful, pleasant or nasty. Jane Goodall was lauded for the incredible work she had achieved with these animals. Her findings were reported around the world, and she won many prizes. About Jane Goodall it was written: “Now we must redefine tool, redefine man, or accept chimpanzees as human.”

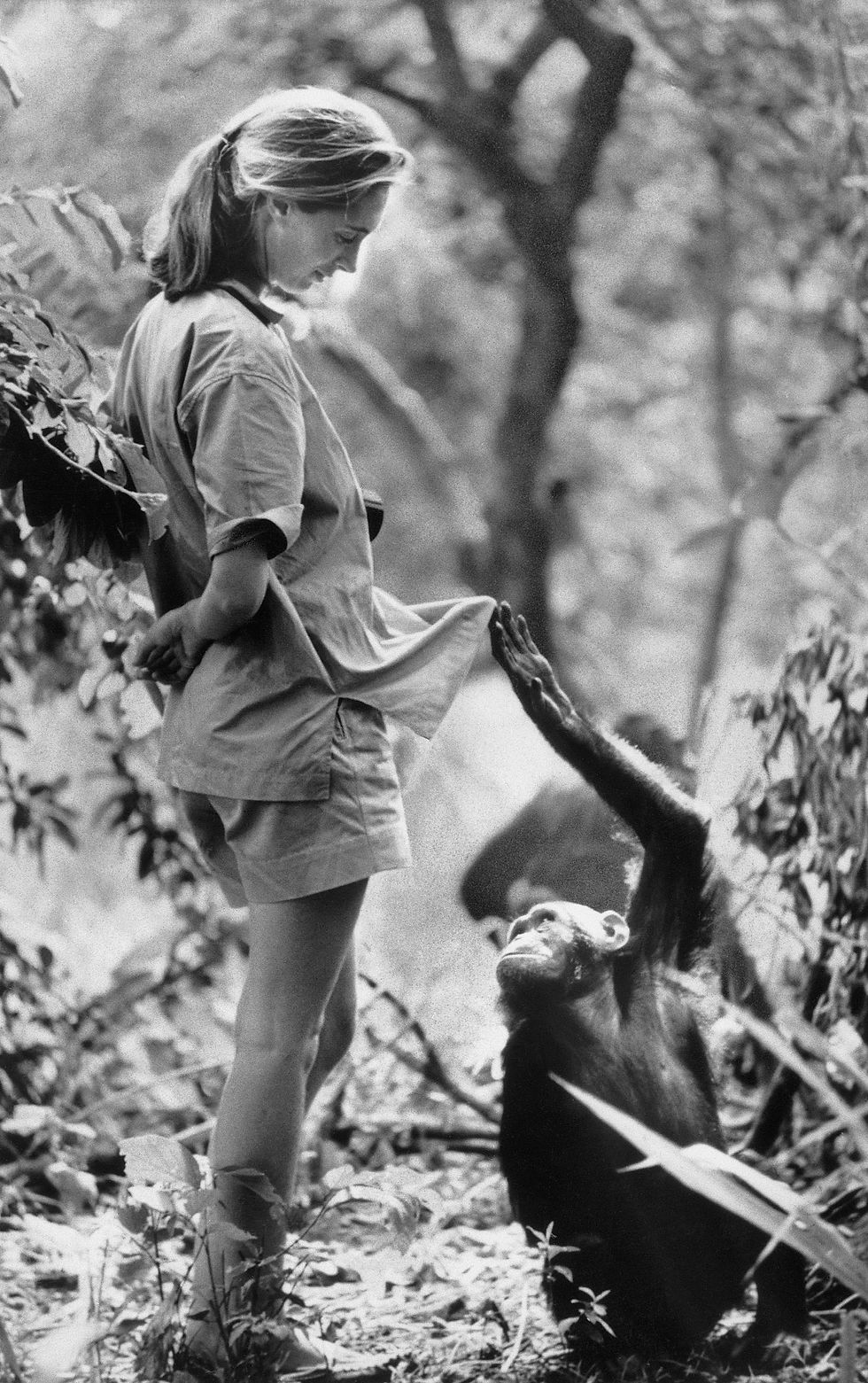

This chimp was a Kahama. He lifted Jane Goodall’s shirt to observe her more closely. After all, Jane was a friend. She was dear to him, and looked after him. “Hugo, quit messing around!” laughed the primatologist. The chimpanzee smiled and looked at her lovingly. It was Jane Goodall who had given him the name Hugo. She had always refused to give numbers to the two tribes of chimps, preferring to give them individual names for her study. Jane Goodall had been a successful diplomat during this war, her gentle ways and kind demeanour having helped ease the tensions between the two sides. They saw in her a heroine, and they worshipped her. Jane Goodall was their guardian; their godmother. Hugo jumped on her shoulders to signal he wanted Jane to take him walking in the jungle, just as Jubilee had done many years before.

Alan Alfredo Geday